Strife is Life

in defense of difficulty

This mid-month letter is about suffering and how it’s good for you, actually, but first, here’s a little song I wrote, complete with a karaoke video. Sing along, scum!

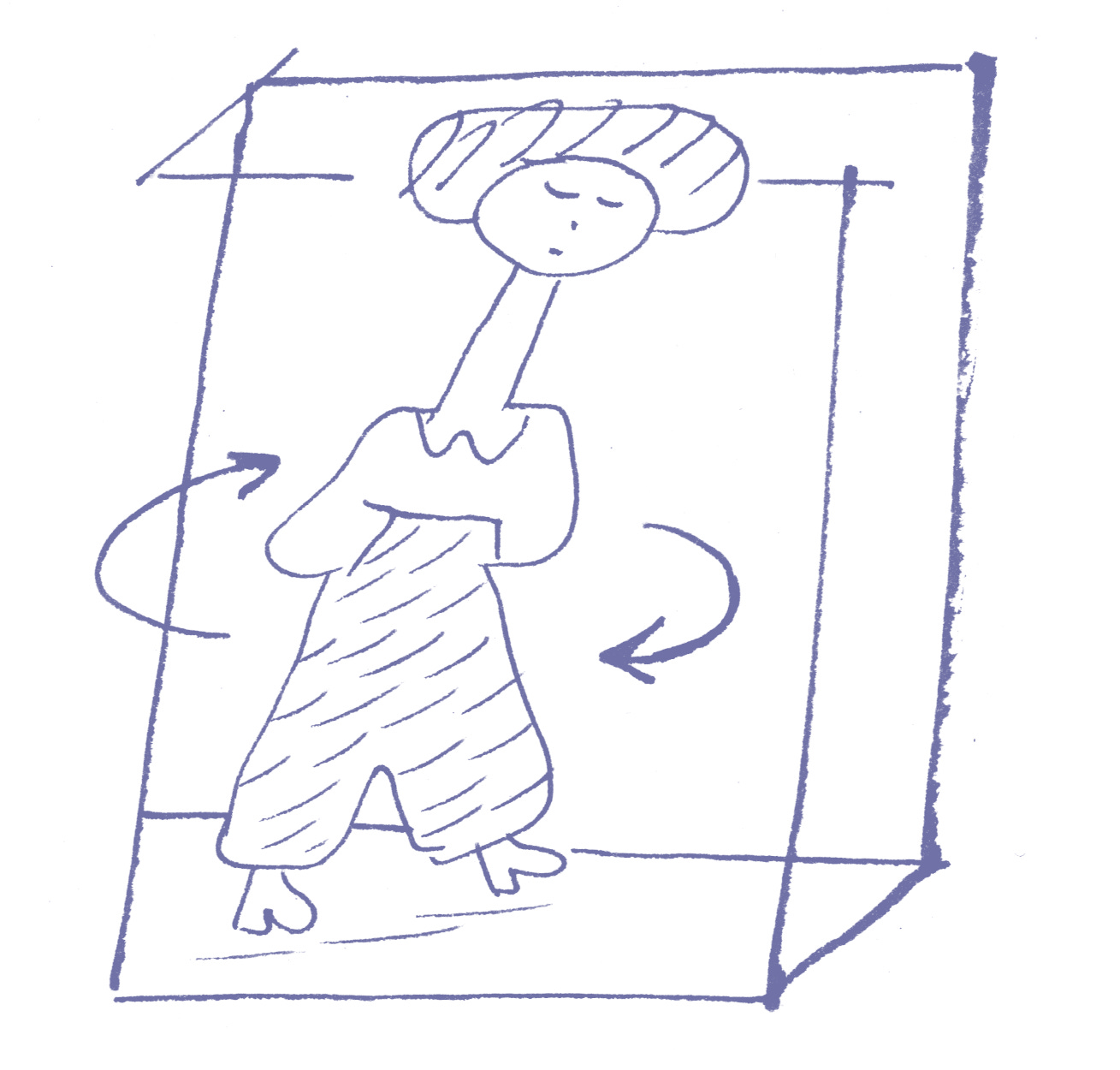

I’ve been slowly exploring Ableton, mostly while producing our little podcast (which itself is partially an excuse to learn a new tool). And speaking of, the title of this post is taken from this 1983 Fall banger.

TREMENDOUS ALPHA, RIGHT NOW

So I had my very unintended 15 mins on Substack recently with this little rant about Ghiblification, complete with a small barrage of comments telling me that it’s not cringey to complain about Ai art, actually.

Anyway, of course it’s a trend, and it won’t diminish Miyazaki’s legacy. The problem as I see it is not with Ai—Chat GPT & co are just the latest tool for avoiding challenges, and that compliance with the safest, easiest and blandest solutions is what brings me down in this world.

Things have been blandifying for a while now, and huge chunks of the population lost any interest in doing anything challenging, and with it, they lost the pleasure of finding their own solutions to overcoming these challenges.

It’s not about the tool replacing something, it’s about the way that tool is used. I’m sure one can use Ai and make something great and original with it—it’s too broad a concept to condemn in its entirety, but unlike previous technological advancements, in its basic form Ai does allow for a totally different level of passivity.

Original work often happens when you figure out your own solution, instead of following the same tutorial that everyone else watched, or asking Ai to make your tedious dreams come true. When everything is pre-masticated, anything you make can only be a straightforward combination of things you already like. People started acting like Ai way before Chat GPT came along. There’s this moronic vision that we all have our great ideas, and simply need to find a suitable outlet for it. By that logic, the work that goes into learning to draw or write is nothing more than an obstacle to the art, but it’s not an obstacle—it is the art itself.

The entire plotline of the book I’m currently working on was originally meant to be just the first chapter, but it kept growing and expanding, and at this point it’s about totally different things. In fact, I don’t have a single project that went as planned, and many of them got horribly derailed, and suffered for it, but it doesn’t matter—better to make an interesting failure, than another dull success.

TREMENDOUS BETA, LATER

Style is the sum of your shortcomings. You copy as many artists as you can, and you copy them wrong, then put a lot of thought and time into analyzing their work (as well as your failed copies), and within those missteps is probably where you’ll find your style.

I had a student once who looked up a photo of ‘a glass of water’ before drawing it. I asked if he genuinely cannot draw a glass of water without reference, and I this was clearly not the reason for googling—he did it compulsively, because the quick solution had become the only one.

It seems counter-intuitive to productivity bros to try something roundabout, when you can save time and effort. But I think we need to force ourselves to pause before hitting that quick fix, and at least consider other options.

And look at the people who obsess over productivity and automation—what do they actually produce? Productivity content, for the most part. And look at people who actually did produce great works of art. Evelyn Waugh wrote Brideshead Revisited on a relatively short break from the Second World War without any masterclasses, spreadsheets and templates.

Did he have a good time doing it? Unlikely, since he was a bit of a miserable fellow, but I can say for myself that figuring out some plot point after a month of banging your head against the wall is the most satisfying feeling I have experienced, and that alone is a much greater reward for the effort than the result itself.

What kind of artist makes work just for the final thing, anyway? Giacometti to me is the exemplary artist in that sense—in his work, the final piece seems to be at best a byproduct of the real thing, which is the process. There’s a good biography of him by James Lord, the one who also wrote A Giacometti Portrait, which is a must, if you want to be even further strife-pilled.

(beyond the paywall, further thoughts on developing style, Ai mistakes, etc)