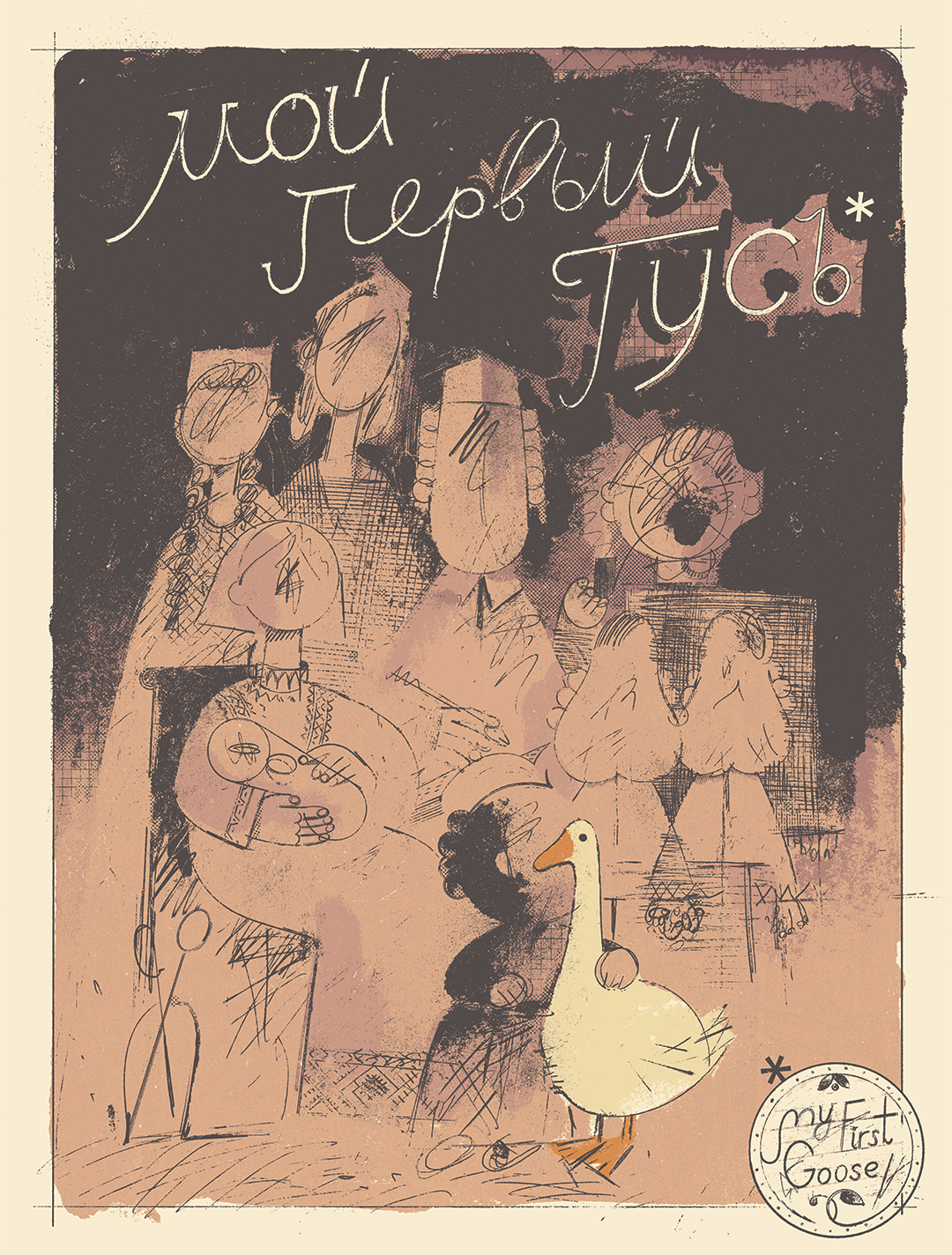

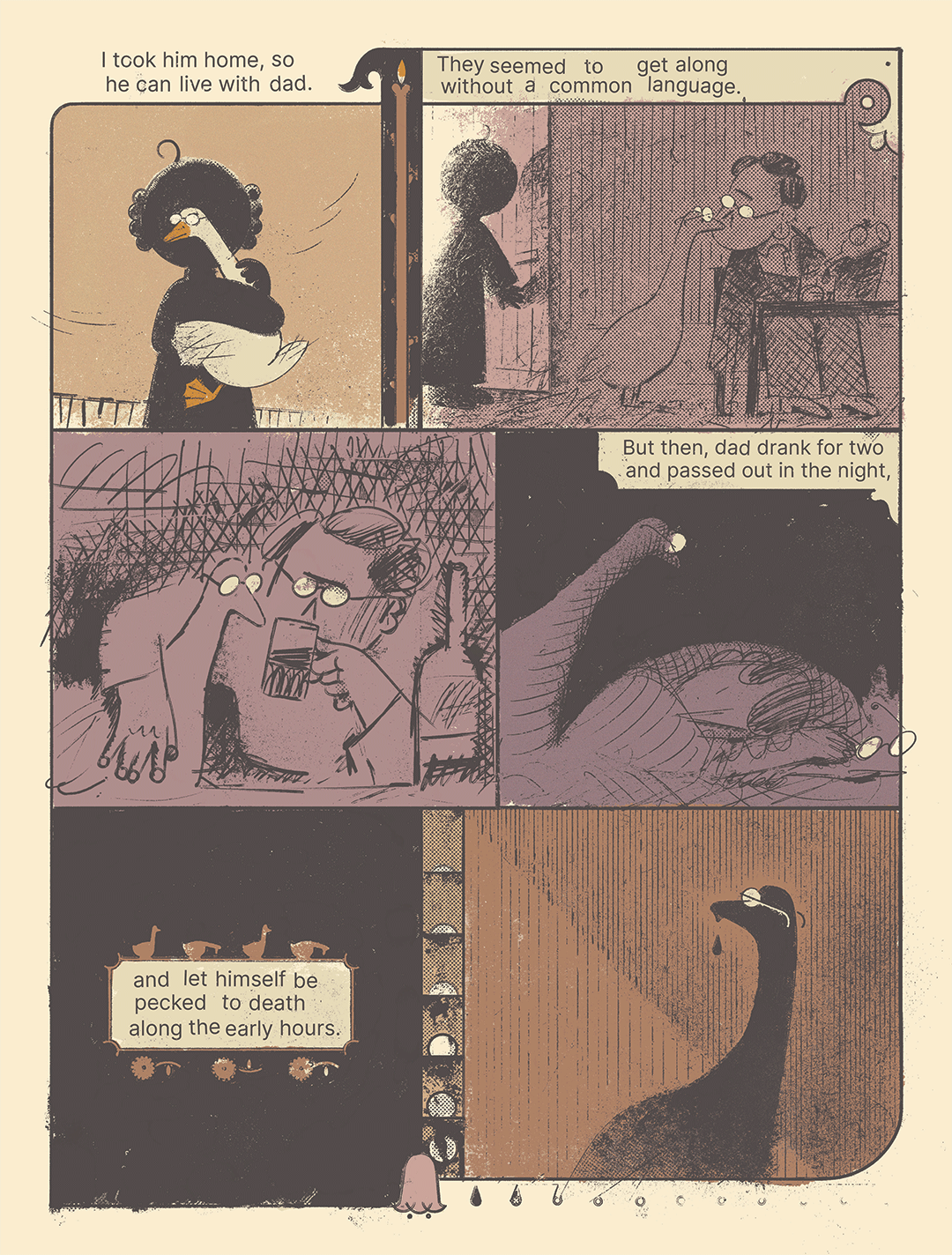

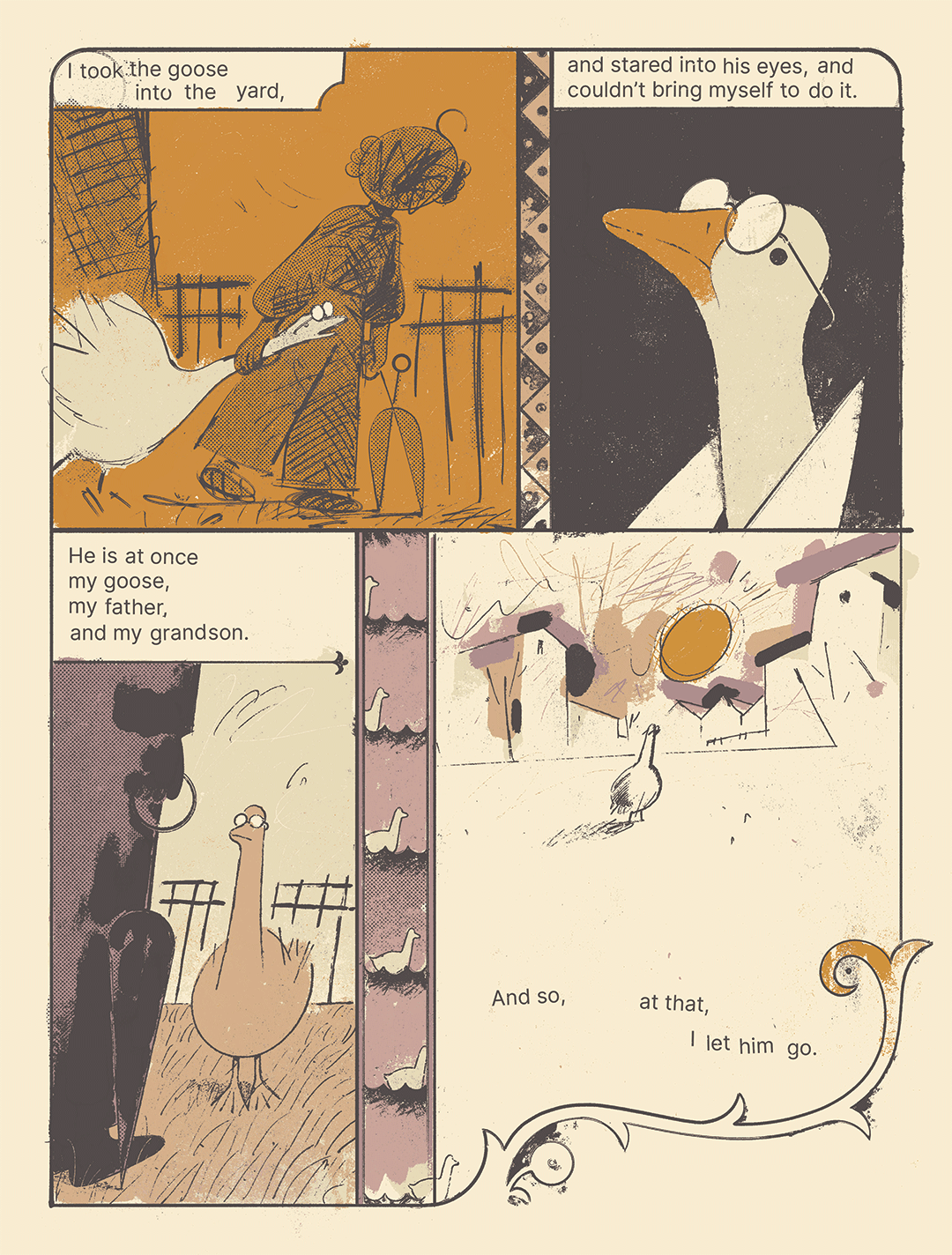

My First Goose

пиктонарративные подвиги древних русов

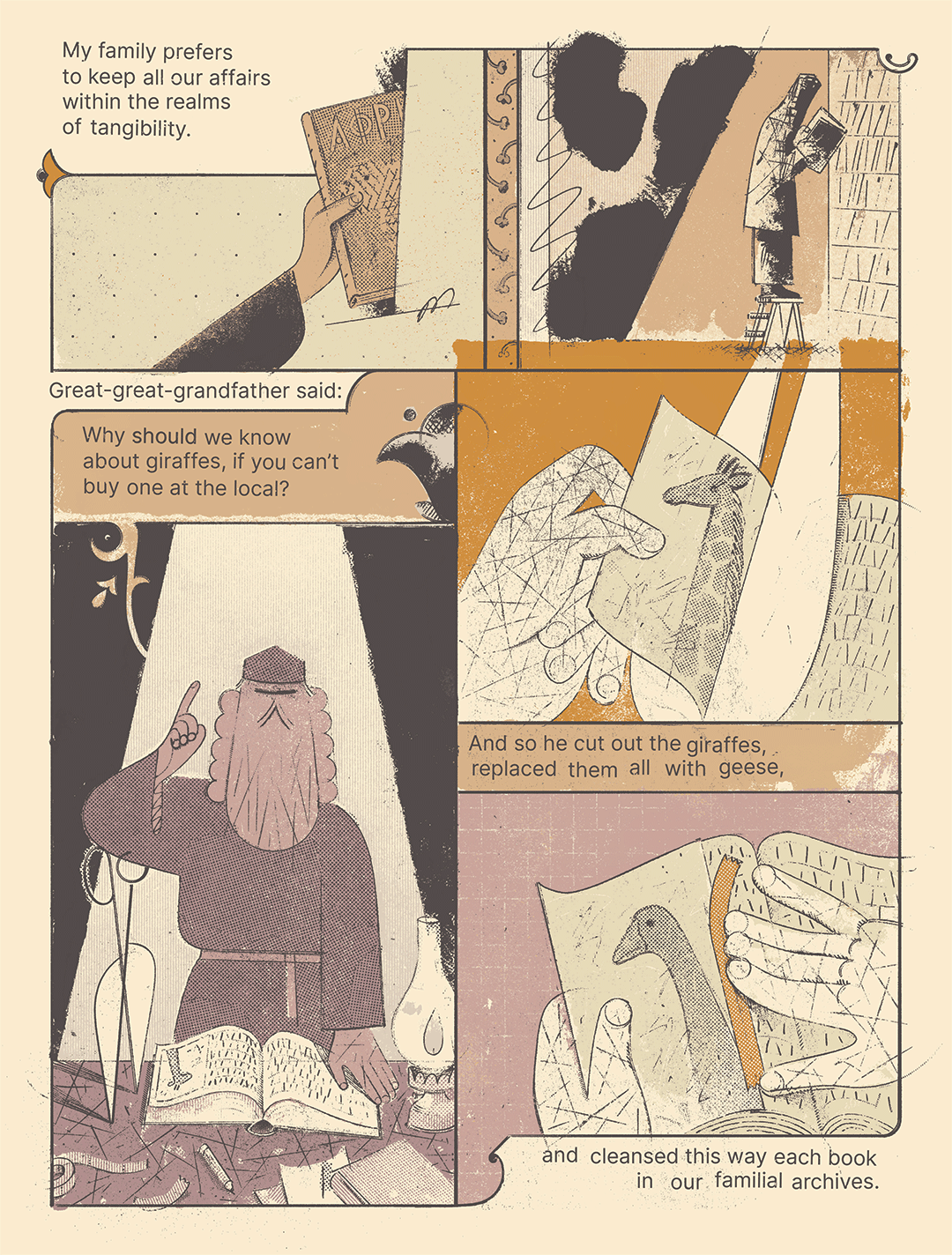

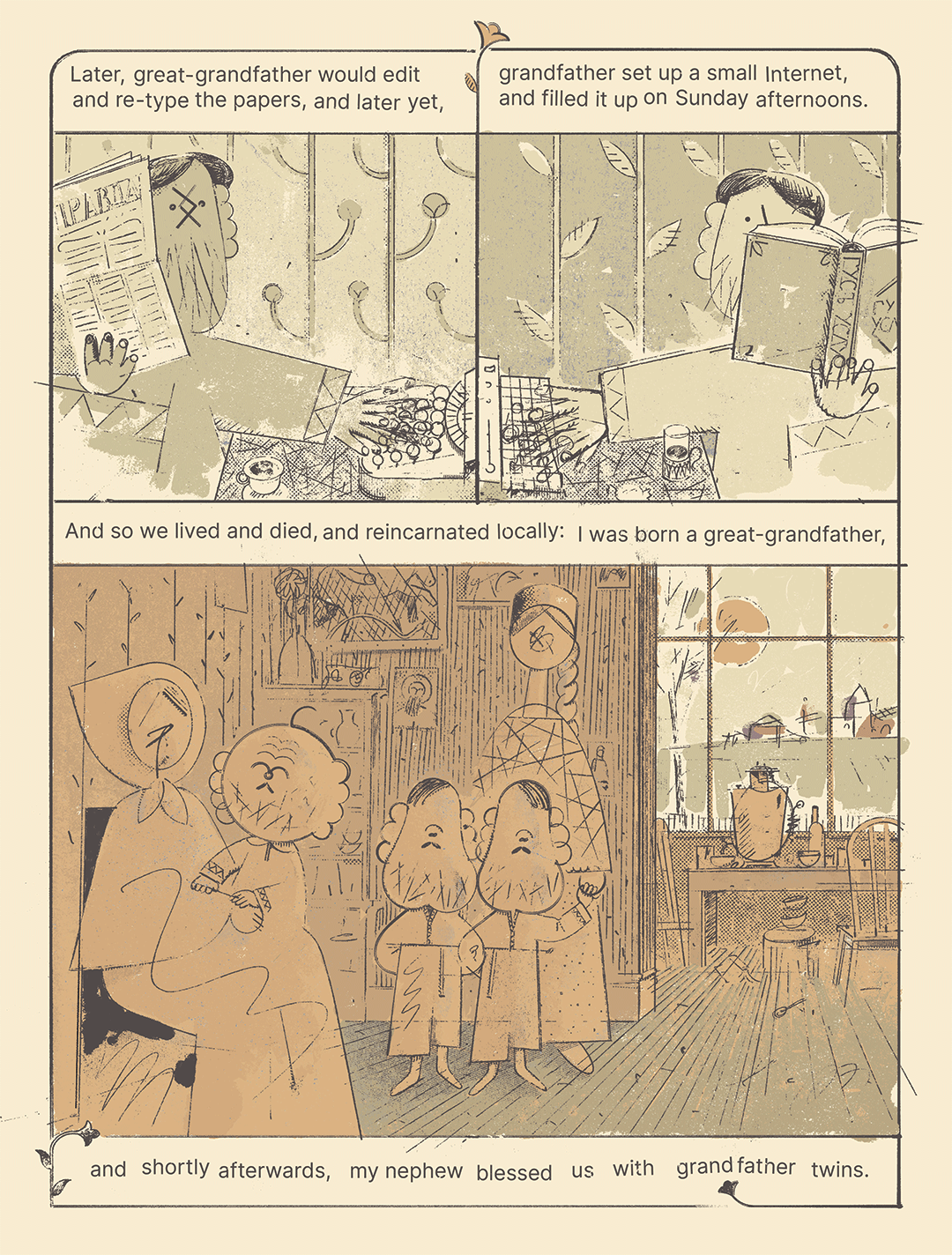

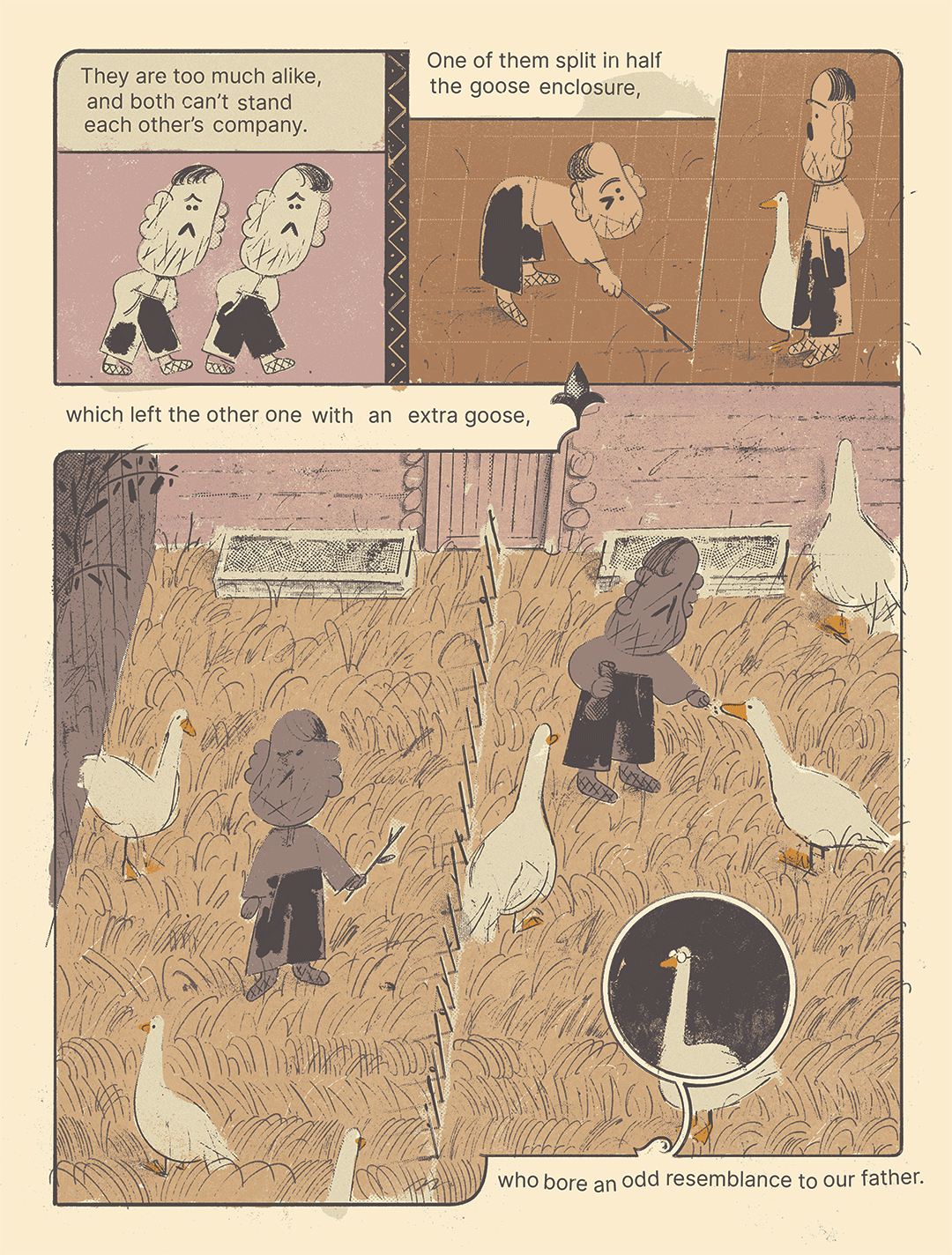

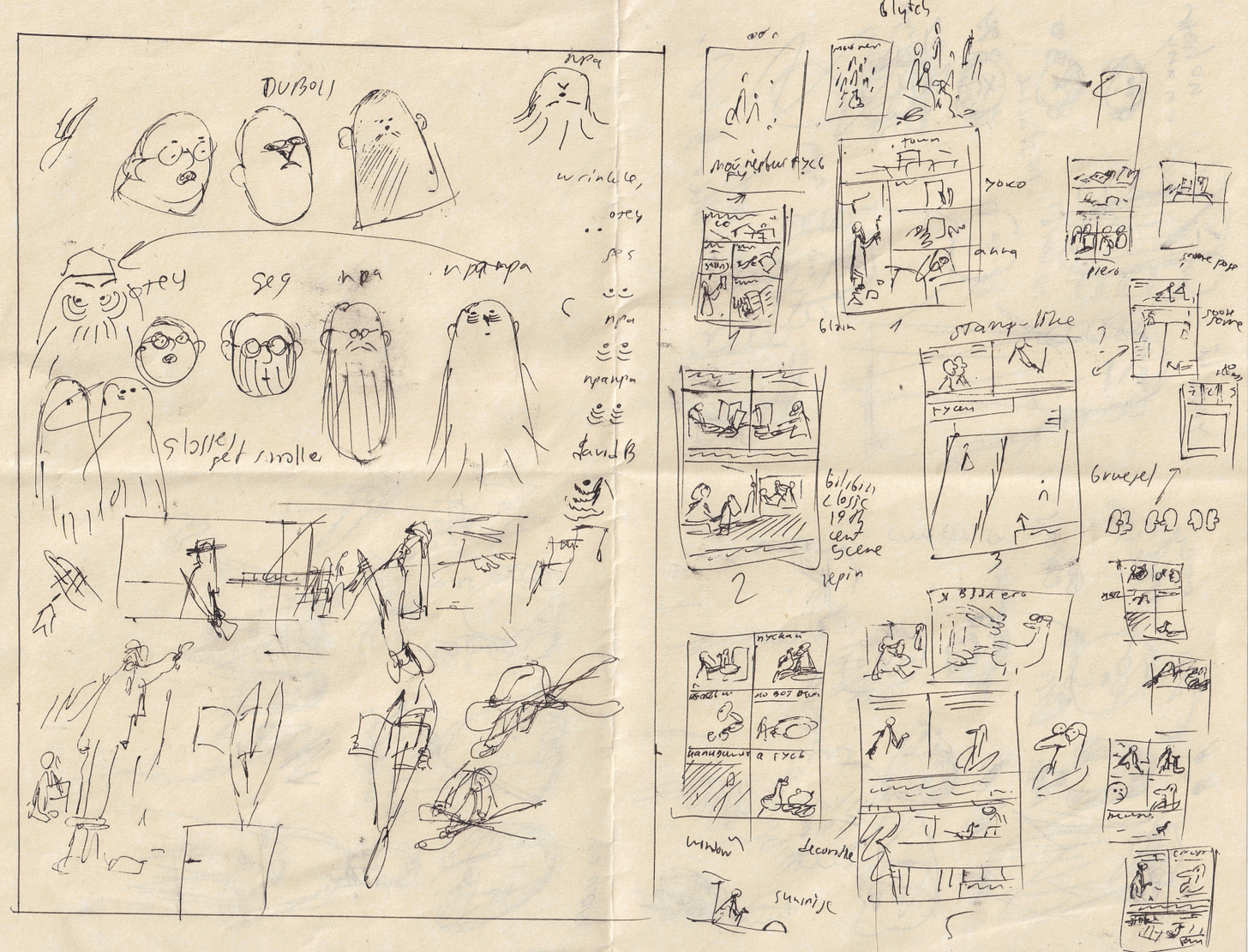

Here’s a short story, just published in Russian in the new issue of Правила Жизни (ex-Esquire) dedicated to the last 30 years of Russian comics. It’s loosely based on the Isaak Babel story under the same name, but more on that later. If you can read Russian, here’s a спешал линк.

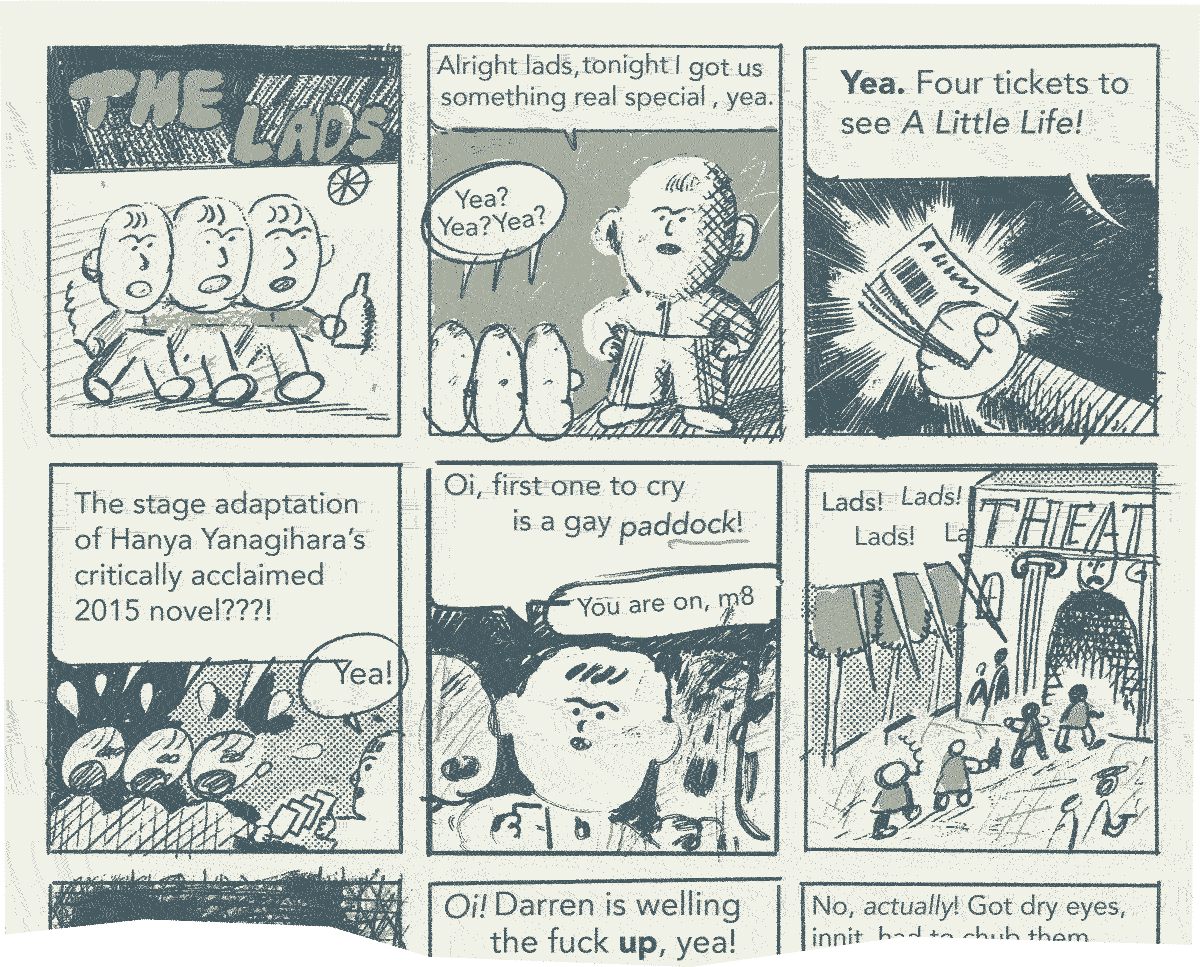

If you want to read more of my sillier comics, sign up for my second paywalled newsletter, and find out what happens to the Lads, yea? Again, feel free to reach out if you can’t afford it, and I’ll gift you a subscription.

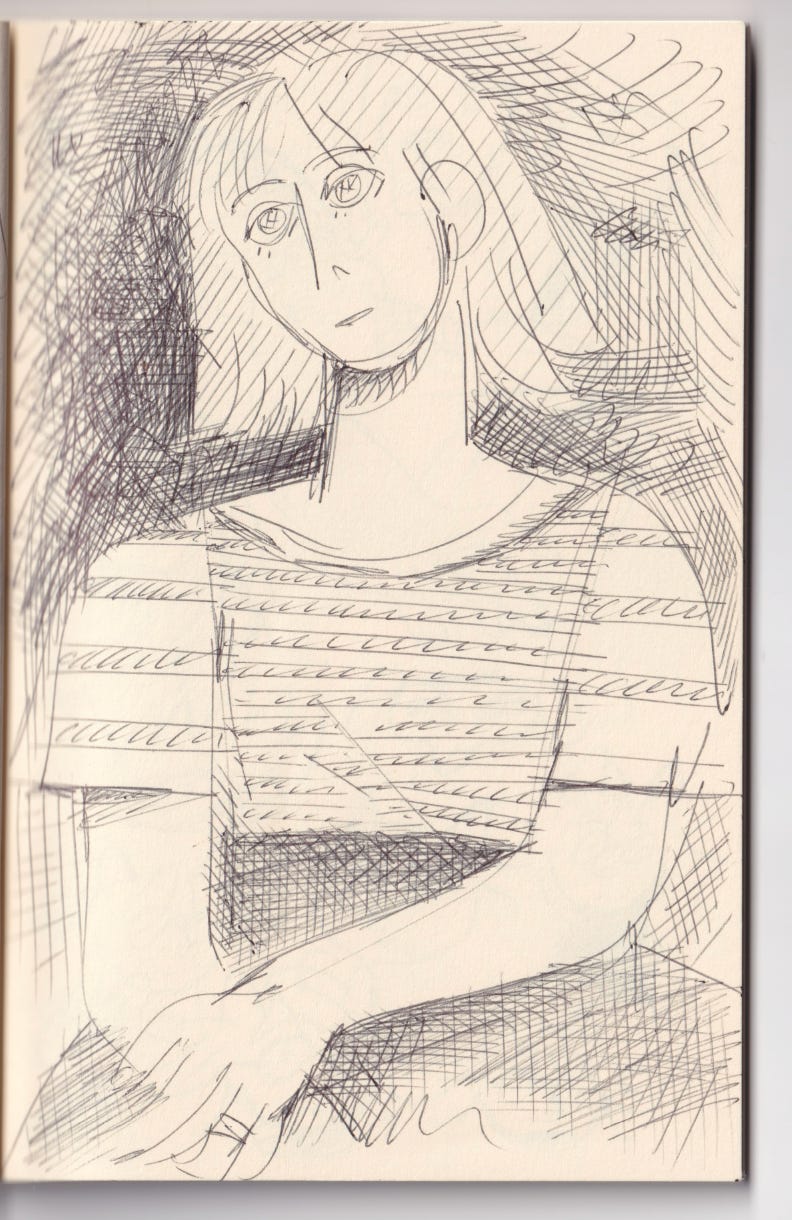

This month’s bonus letter also features a bunch of sketches from my recent trip to London and Wales. Nice to touch paper again. To hell with grass!

Anyway. All this difficult translating made me lusty for more, and I decided to give the original My First Goose a go. Babel is notoriously untranslatable, so my take is very much an interpretation of the text, rather than a faithful translation.

MY FIRST GOOSE by ISAAK BABEL

Savitsky, commander of the sixth division, stood up when he saw me, and I marveled at the beauty of his enormous frame. With the purple of his breeches, his crimson cap off to the side and the medals on his chest, he rose and split the hut in two, like a banner splitting the sky. He smelled of perfume, tinged with a treacle of soap. His long legs stood like a pair of girls, strapped to the shoulders in shiny jackboots.

He smiled at me, struck his whip against the table, and reached for the order that had just been dictated by the chief of staff. It was an order for Ivan Chesnokov to advance with his appointed regiment in the direction of Chugunov-Dobryvodka, and, on contact with the enemy, have them destroyed…

“…said destruction,—the commander began to write, and filled up the whole sheet,—I entrust to Chesnokov himself, up to the highest measure, and I intend to kill him on the spot if he fails to do so… an intention which you, comrade Chesnokov, having worked with me on the front for many a month, should not have reason to doubt…”

Savitsky signed the order with a flourish, tossed it to the orderlies and turned his eyes—grey, dancing with mirth—towards me.

I handed him my assignment to the division staff.

—Wrap it up!—said the commander. —Wrap up the order and sign up for provisions, save for the private ones. Can you read and write?

—Yes, —I replied, envying the iron and flower of his youth, —I’m a graduate of the University of Petersburg…

—One of the kinderbalms, —he shouted, laughing, —glasses on his nose… pathetic! They send your lot without asking, then you get cut down for your spectacles. Think you can manage it here?

—I’ll manage, —I said, and followed the quartermaster into the village to find a place to sleep.

The quartermaster carried my small suitcase on his shoulders, and the village street lay before us, round and yellow, like a pumpkin, while the dying sun let out its pinkish breath into the sky.

We came up to a hut, painted with garlands. The quartermaster halted and said, with a sudden guilty smile:

—Nothing to do about it, what with the glasses. Round here, a man of highest order will get rinsed out… but if you go and ruin a lady, a nice honest lady… then they treat you right…

He dawdled with the suitcase on his shoulders, came close to me, then halted in confusion, and ran into the nearest courtyard. There, a group of cossacks sat on the hay and shaved each other.

—Now then, —said the the quartermaster, setting the suitcase on the ground. —In accordance to comrade Savinsky’s orders, you must take this man into your quarters, and no nonsense—this man has been injured in the field of learning…

The quartermaster reddened and left without looking back. I lifted my hand to the cap and saluted the cossacks. A young man with drooping flaxen hair and a handsome Ryazan’ face walked up to my suitcase, and threw it out the gate. He then turned his back to me, and, with a deliberate cunning, began to make unseemly sounds.

—Zero-zero caliber, —yelled the older cossack and laughed, —rapid fire…

The young man exhausted his humble craft, and left. Down on all fours, I began to gather my manuscripts and my tattered clothes. A pot of boiling pork fumed like a chimney of a distant home, muddling the loneliness and hunger in me. I covered my broken suitcase with hay, and rested my head on it, intending to read Lenin’s speech at the Second Congress of the Comintern. Sun fell on me through jagged hills, cossacks walked over my feet, the young man mocked me without respite. Beloved lines dragged themselves towards me in convoluted pathways, but couldn’t reach their destination. I put the paper to the side and came up to the landlady, who was spinning yarn on the porch.

—Listen, —I said, —get us some grub…

The old woman raised the spilling whites of her half-blind eyes and lowered them again.

—Comrade, —she said, after a silence, —I want to hang myself, what with all this...

—Mother of Christ, —I muttered with annoyance, and shoved the old woman to the side, —no use talking…

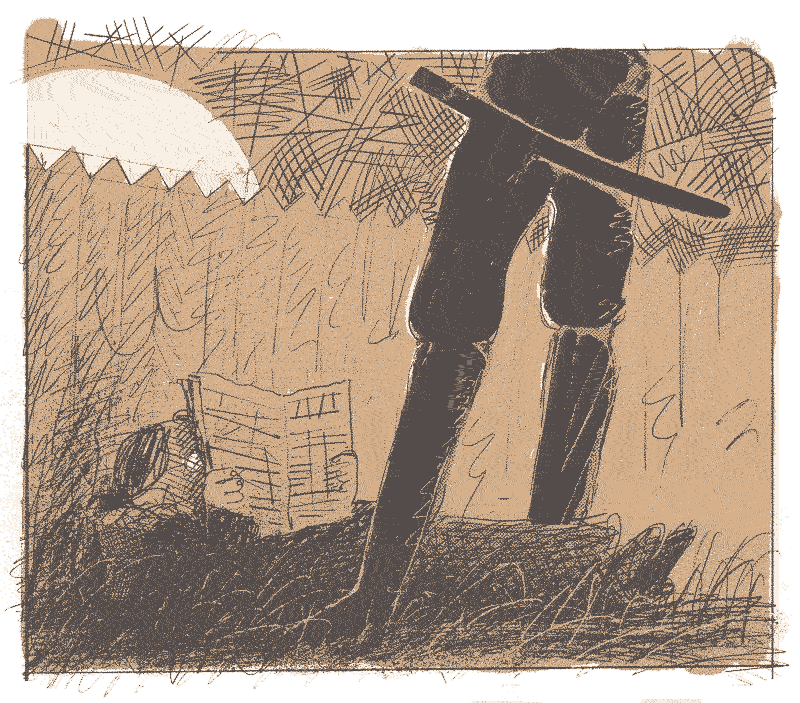

Turning, I noticed a sable beside me. A stern goose meandered across the yard, calmly grooming his feathers. I chased him and pushed him to the ground. His head crackled under my boot, split open and oozed. His white neck was splayed out in the dung, and his wings twitched behind the dead body.

—Mother of Christ! —I said, digging into the goose with my sable. —Here, roast him for me.

The old woman, illuminated by her blindness and her spectacles, picked up the bird, wrapped it in her apron, and dragged it to the kitchen.

—Comrade, —she said, after a silence, —I want to hang myself, —and shut the door behind her.

Meanwhile in the yard, the cossacks were already gathered around their pot. They sat motionless, like priests, and paid no attention to the goose.

—He’s alright, —said one of them, winked, and helped himself to a spoonful.

The cossacks began their dinner with the restrained elegance of simple men, who found respect in one another. I cleaned the sable with sand, walked out the gates, and, feeling uneasy, returned again. The moon hung over the yard like a cheap earring.

—Brother, —said Surovkov, the elder of the cossacks, suddenly, —come sit with us, till your goose is done…

He took out a spare spoon out of his boot and handed it to me. We had some of the soup and finished up the pork.

—Anything in the papers? —asked the young man with the flaxen hair, and made room for me to sit beside him.

—Lenin is in the papers, —I said, taking out a copy of Pravda, —Lenin writes we have a shortage everywhere…

Loudly, like a deaf man in triumph, I read Lenin’s speech to the cossacks.

Evening swathed me in a soothing mist of twilight bedsheets, and I felt a touch of mother’s palms on my burning forehead.

I read on and rejoiced, anticipating the mysterious curve of Lenin’s straight line.

—Truth tickles the nostril, —said Surovkov, when I finished, —but where do you find it? This man strikes it out, like a hen pecking the grain.

That’s what Surovkov, the squadron commanded, said about Lenin. We then went to sleep on the hayloft. The six of us slept together, warming each other with our tangled legs, under a roof speckled with holes that let the stars in.

I slept and dreamt of women, while my heart, crimson with murder, crackled and bled.

PS. Yes, the girls-in-jackboots line in the first paragraph is just as weird in Russian.

PPS. I deliberately did not reread the Babel story in preparation, as I wanted to rework it from memory alone, and let it be corrupted however it wants, but there are a few unexpected connections like the Pravda newspaper—I had no memory of it in the story, but here it is, in both.

PPPS. I chose to gender the goose ‘he’ in the translation, rather than ‘it.’ I imagine it can sound off to a non-Russian speaker, but it makes the act so much more real, no? In Russian it works naturally, since the noun for ‘goose’ is already a ‘he.’ In English, ‘its head crackled’ is just not the same as ‘his head crackled.’ Needless to say, I ran into the same issue first with my goose story, and chose to do the same thing. Later on, though, when the bird is dead, I went to ‘it.’ No idea if it makes sense, or simply reads as a mistake (the Pushkin Press translation goes all ‘it’), but this is all a bit of a personal exercise anyway, so who cares.

PPPPS. The final word of the story is ‘leaked’ or ‘oozed,’ which is what I used for the goose murder scene. It would make sense to use the same word, of course, but there’s a much greater ambiguity in the Russian word, and ‘bled’ is just stronger. Babel uses a lot of repetition that I preserved in some places and edited out in others. Certain translators of Tolstoy have been accused of neutering and softening his language this way, and it’s fair, but Babel is more complicated—he is at once blunt and ornate, and his repetitions don’t always translate out of Russian, and can sound too tied-up.

PPPPPS. Babel had a golden rule—no more than one adjective per noun. It’s curious, though, how hard he struggles against his own imposition, and how much he twists the words around the constraint. It’s not simply a call for simpler language, as I see it, but an attempt to circumvent the cracked kettles and write these almost abstract descriptions that work perfectly well without actually making much sense (legs-as-girls, again).

That’s it for this month’s newsletter. Thanks for reading, please subscribe and share and all that jazz.